Listener – July 15, 2000

A few months back in the wee hours of the morning I was tussling with some raw unturned thought that wouldn’t sleep. National Radio’s “All Night” programme was barely audible on my clock radio, when, ever so quiet, there came to my ears the unmistakable velvety voice, albeit a little shakey, of veteran broadcaster Alistair Cooke.

I can’t remember the exact subject matter of this particular “Letter from America” – something about Hillary Clinton’s bid for the Senate, spiced perhaps with anedote from a New York taxi driver . . . or was that another letter? It wasn’t exactly what Cooke was saying that comforted me on that particular night, but, rather, the grain of his well-travelled voice and the sense of assurance that he carries his burden lightly.

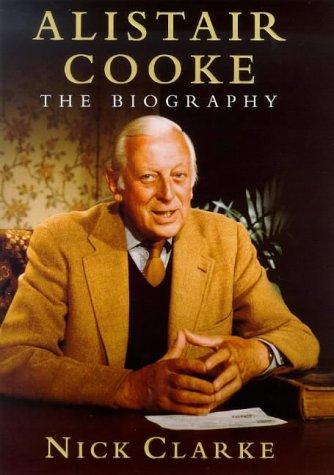

Now 92, Alistair Cooke has been in turn a special correspondent for the Times and the (Manchester) Guardian, written 17 books and, among other projects, created one of the most complete televised histories of the US. But it is for his weekly “Letter from America”, broadcast in 52 countries, that he is best known. Begun in 1947, it is an amazing broadcasting achievement. And he ain’t finished yet.

Though the author of this biography is a noted broadcaster himself, Cooke wasn’t initially keen on the project. As crops up again and again in this 500-page tome, he has always liked to be in control, and if a project is not his idea he has to be courted very carefully (though he himself has shamelessly courted the US’s rich and famous in order to clinch a good yarn).

In his early days as a journalist Cooke was notorious for filing his stories at the last minute, much to the the chagrin of his English masters, but he wrote like a dream and got away with it. To this reporter’s ear he writes and talks like a poet, weaving across time and space with frightening confidence. His acting days at Cambridge University taught him timing and the power of a well-placed quote. Add descriptive prose, at times the equal of Hemingway, and the empathy and wisdom of poet William Carlos Williams (“no ideas, but things”), and you get passages of pure word music such as this:

“Hemingway took the daily speech of the non-literary American and turned it into literature. He started to knife away all the fat he could find in language; he leaves only the heart and muscle and nerves – the verbs and the nouns and the adverbs. And all their living movement, their circulatory system, is the the prepositions – the ons, and fors, and withs, and bys, and froms.”

Writing for radio required a different skill. Cooke wanted it to sound as if he was speaking to two good friends: “Writing for talking is no less than abandoning architecture (written structure) altogether and trying to imitate the movement of a bird or a river.”

He did the odd broadcast for the BBC during World War II and BBC executives accused him of “speaking too fast, breathing so hard he sounds like a racehorse . . . and sounding childish alongside other British commentators”.

Nick Clarke points out that a psychiatrist Cooke consulted for two years after the break-up of his first marriage (to Ruth Emerson, the great-niece of the poet/essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson) “helped him adopt the principles of his broadcasts – letting his unconscious lead him from one thought to the next without trying to enclose it in an intellectual straitjacket. In those terms ‘Letter from America’ would become the first (and perhaps only?) Freudian radio talk.”

Cooke claims, though I find it hard to believe, that when he sits down to write each week’s letter he has no idea what he is going to say, only that it will “conversational in presentation, complete with the syntax and quirkiness of spoken English”. This manifesto was in part inspired by listening to the likes of Aldous Huxley and W H Auden, whom Cooke says “had no idea of how to speak on the radio”. The Freudian requirement was that he should “be himself, rather than some pale imitation of any other broadcaster”.

Following this credo has made him one of the great commentators on American life. I’m reminded of an essay entitled “The Grain of the Voice”, by the French philosopher Roland Barthes. In it, he says that when he went to hear a Russian opera singer he didn’t hear a single opera singer but the whole of Russia.

When I hear Alistair Cooke I hear across the great divide Mark Twain conversing with Charles Dickens, wondering what the hell to make of Quentin Tarantino.

LITTLE-KNOWN FACTS ABOUT ALISTAIR COOK:

* He was born in Salford, Manchester, the son of an iron fitter, but he didn’t wish it widely known, calling Salford “an appalling place”.

* He was Alfred Cooke for the first 22 years of his life before adopting the more refined “Alistair” in 1930.

* At Cambridge University he did his thesis on Katherine Mansfield.

* Among his many friends have been Charlie Chaplin, Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart. He had a liking for Lyndon Johnson but didn’t much care for John F Kennedy. His favourite American author is H L Mencken.

* Biggest professional disappointment: that a personal view on the life and works of Mark Twain was never televised. He considers it his best work.

* Cooke’s son Johnny (a Western novelist and folk musician) was Janis Joplin’s road manager. He was the one who found her dead from a heroin overdose.