Landfall Review Online – July 1, 2017

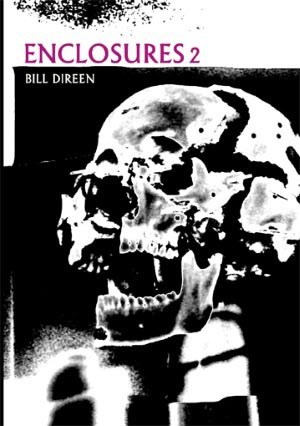

The reconstructed skull* on the front cover of Enclosures 2 is a fair signifier of the book’s content: floating in negative space, the skull’s fissures give the impression of coastlines, continents, isles, waterways. Also Life. And Death. For two decades Bill Direen, novelist, poet and musician, lived in and travelled between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Living in Paris, he writes, is due to the love of a French woman. But in his book he’s mostly a writer alone, in a room, in a crowded Metro carriage, on a night train to Germany, or aboard one the Cook Strait ferries. He now lives in Dunedin.

From ‘The silence of migratory birds’:

My face still possesses something of me, as people remember. It has aged, revealing its care and the nature of its thoughts, and it contains something of them, the once met, that rubbed off on me. Something of you perhaps, and something of people I knew in Germany. We are each other.

His ‘novel’, we’re told, continues the same cross-genre approach favoured in an early novel and used in purer form in Enclosures (2008). I saw Bill Direen perform once, perhaps in the early 1980s in a theatre in Wellington’s Courtenay Place, playing guitar, singing original material. The context of the performance and the venue have gone, but I recall being impressed by his thought-provoking lyrics, the energy of the gig. This is the first time I have read one of his books.

From ‘Republics at peace’:

Occasionally there will be a suicide, a murder, a fire. Or someone who has been sleeping in the stairwell will ring at a door, stepping back so as not to frighten the occupant. He may ask for water, or food.

‘Europe, New Zealand’, the novel’s opening section, occupies half the book’s pages. Derived from notebook entries and ‘the surviving parts’ of a failed project, this section comprises ten pieces: ‘Notebooks’ (‘In Paris one can develop a kind of relationship with people one never meets’); ‘The silence of migratory birds’; ‘Experimental’ (‘‘I’ is the genus that owes and fails itself … antigen voyager of no Harbour’); ‘Republics at peace’ (‘News of the week is the same as last week: the spread of Halal; the leader of the Really Left losing popularity; the National Front calling for the death penalty’); ‘Landscape with too few philosophers’ (‘I am writing on what was once known as The Island. It is a port village accessible by a road crossing an area of drained swamp’); ‘Owens & Owens’ (‘There are two of him. The one who died and the one who did not die’); ‘Radio play for a defunct station’ (‘One is never exactly on the station. You can hear more than one programme. Old programmes are running on and on, drifting’); ‘The ice-sellers of Montmartre’; ‘Circle, summa autem’ (‘Water is always drawing expanding circles from source points. I like to pass free time by a Spree or a Yarra, a Charles, a Seine, a lagoon or a harbour’); and ‘Where do you come from?’

Four sections follow: ‘Centre’, a long poem written during a residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre in Devonport (July 2010–January 2011); ‘Stoat’, a short story in five parts about a son’s return to Dunedin and the making of an album, with a shapeshifting ending; ‘Canal City’, a ‘utopia’ in the form of an imagined futuristic Christchurch that has rejected its squarish past to be rebuilt following the old course of the Avon river; and ‘Survey’ (in two parts: First Voyage and Second Voyage), a strange piece about conflicting cultures on body surfaces. To ease us into the ‘zootopia’ we’re informed that Captain Cook and his men’s bodies were burnt, with his men’s limb bones divided among inferior chiefs, while his head was given ‘to a great chief called Kahoo-opeon, the hair to Maia-maia, and the legs, thighs, and arms to Terreeoboo’.

There are crossovers between imagined and real places. Themes repeat in different styles, contexts, times, zones and hemispheres, as in this, from ‘The ice-sellers of Montmartre’:

I leave the place where Napoleon never marched, where the tide sweeps shelves on beaches less and less deserted. We are flying over the Pacific, a place of epidemics, mass murder, cannibalism, tribal and imperialist massacres, tsunamis, neighbourhood distrust, death-by-drowning, hegemony, nepotism, a distinct third gender and corrupt elites, black, brown and white. And that is only the beginning of the 30-hour journey.

Which contrasts with this, from ‘Republics at peace’:

Once again, I will be leaving this city [Paris] where I have never felt so out of place, nor so at home. I will soon be living in a suburb called Lookout Point, home of a species of rare annelid, on what is possibly the worst-maintained street in the city of Dunedin.

Which leads us to Stoat, who works the night shift for the Department of Conservation. He is woken by the sound of his son rapping sharply on his door. Skink, recently returned to these isles, is looking for digs. He is given the run of a grotty basement room; there are ‘card boxes, threats of prosecution in absentia … Waterlogged porn and reproductions of men surfing print onto each other. A reliquary of dead dolls and comic book figurines …’

Enter Goat, Skink’s brother. ‘If Goat redeems his physiognomy from stereotypes of diabolism and stupidity, he is on the verge of subscribing to another, urban rock poet … He speaks bitterly, he speaks inventively whether he has an audience of twenty or one. He leaves arrears at a firetrap hotel and moves in …’

Stoat ‘sets bait and and gathers cadavers. He lays them out like life’s lost alphabet.’ Skink and Goat work on their music while Stoat is out and about:

They are monkey-pink tattooed creatures of contradictory homogeneity generating noise and distortion, compression, phase and echo … The album will decry the heritage of the shanty town, murder for gold of lucrative calculus. The album’s rage is always fomenting …

The album is the egg, the gig, the novel of enclosures, its mirage, its making carceral. The tracks are all in the cellblock with us. Cell as beginning of freedom, of riot, of fire … Ungendered infants emerge, self-reproducing parents expulsive themselves in kick beats and splatter … The album is cry of pain in ejaculation … Skink and Goat are as one, the winged fascinus of a betrayed Caesar, the inner flaps of a patricidal Agrippina. They have no/all genders … Stoat draws the two figures back inside him. They are the primacy of his teens, their idiocy and unsuspected sagacity. Their screams ignite … Goat is the dark blood sacs in Stoat’s sinuses, his clouding sites of gang beholding …

Eventually, Stoat becomes all in all with the ‘Stoats of Otago’:

They are the makers, the record labels, the buyers and the audience … His life is no longer a case of isolated alterity. There is no other, but others that are himself. They emerge from Death Hill, his witnessed self receives them born out of rock … There is one master, and, as ever, there is no master … He cycles to night shift.

In ‘Republics at peace’: ‘[Direen] used the word autobiography. A writer hangs himself upon one. What I am writing here, I am told, is an auto-fiction, which sounds to me like something a Calvinist would disapprove of.’ He also has a take on whakapapa: ‘We do not descend from a single parent, but from many which may have belonged to more than one species. Even the pope has said as much, and he has a better library than I do. But we also descend from ourselves, from something that no longer exists.’

And in ‘Radio play for a defunct station’, ‘where there are extracts from abandoned novels’, he points to nature’s gender bending: ‘Some creatures are male in the early stages and they become female later on, and vice versa. I have heard her voice speaking lines of male.’

It is a pleasure to glide over and dig into Direen’s well-made sentences; one has favourite parts/sections, such as ‘Stoat’, which showcases the depth and uniqueness of Direen’s creative thinking, and the more conventional (but no less creative) memoir style of ‘Europe, New Zealand’. This revelatory passage from ‘Notebooks’ sees the author in Paris:

I have been walking, holding myself differently. Singing antiphons of country, folk, ballads, with strains of improvisation. And suddenly I am living as if life had been denied me. That’s the only way I can describe it. To cry out, to sing. To weep before paintings I have only ever examined for their clues and narratives. To be no longer the person I was before. To live unafraid of Him, even when on the same sidewalk as Him, the one who looks so tired, yet who has a curiously benign and understanding expression. Even when face to face with him in a crowded Metro carriage. Death.

*Front cover photo, from ‘Going to the Museum with Dad’ (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris): Owen Slatraigh, 2008.